This post is part of a series where Joel Tosi and I write about the course we are developing titled “The Thinking Leader’s Toolkit”.

This week we apply causal modeling to something different.

For many of us, the idea that fear has no place in the workplace is obvious. It’s not a new idea. Deming named “Drive out fear” in his 14 points on management decades ago.

There are some, however, who think that intimidation is a valid management technique or that a little fear is motivating. They’re wrong, of course. (Just ask Sully and Mike from Monsters, Inc.) But WHY are they wrong? Is this something a causal model can help us explore? It turns out that yes, yes it can.

Let’s take a look at the blame cycle, a common driver of fear. It starts with the idea that problems can be attributed to individuals. Imagine something bad has happened, like a production incident. The fear-and-blame oriented boss demands to know: “WHO IS AT FAULT?!?”

“Not me!”

“Well it’s not my fault!”

“I certainly hope you’re not trying to put this all on me. I just ran the script. They wrote it!”

“The script didn’t cause the outage. Your configuration did.”

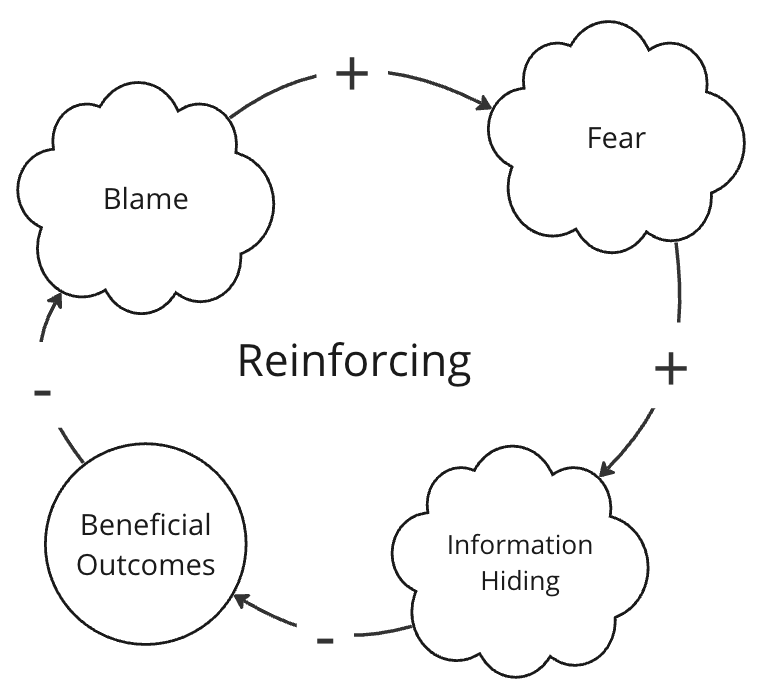

The cycle has begun. A game of pin-the-blame-on-the-scapegoat ensues. Fear levels rise, along with defensiveness and denial. Some seek to hide any indication of their involvement. They want plausible deniability. Others cherry pick data in order to make themselves look good.

At this point, any data or metrics coming out of the organization are questionable. The data is likely to be distorted to make a given constituent look good, or at least dodge blame. That means the blame-oriented boss can’t get trustworthy data. That in turn leads to terrible decisions (because good decisions require good data). Terrible decisions lead to bad results. The cycle continues.

It’s ironic: trying to pin the root cause on an individual to root out the problem actually creates more problems. Worse, the cycle is reinforcing. It continues as a downward spiral as long as management believes in blaming individuals and instilling fear.

If you work with someone who tends to blame others and create fear, you could try using this model to explain why that approach causes more harm than good. Unfortunately they’re unlikely to change their approach. It will take more than a model to change their underlying philosophy.

So what’s the point in creating the model?

Sometimes the benefit of a causal model isn’t helping someone else see something that’s obvious to you, but rather helping you see exactly why your intuition is right. That validation might just be the confidence boost you need to keep going.